Since writing part one of this series, Germar Rudolf has released a comprehensive book on the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg (IMT), which I highly recommend. In this article I will share some of the information about the Soviet show trials that predated the IMT using information from this book. If this article piques your interest, BUY the book and READ it!

If you believe prior trials meant the IMT was right to accept Allied reports as factual (see image below), you’d be wrong. All of the pre-trials against the Germans were conducted by Germany’s former wartime enemies. This victor’s justice might have been common in the past, but it hardly serves as proof that the defendants actually did what they were accused of as the imbalance of power meant they had no protection against false accusations.

The Soviet Union didn’t even wait for the war to be over before they began their show trials. The first of these trials was the Krasnodar trial, which took place between the July 14th and 17th, 1943. Its purpose was to make an example of, and punish, eleven local Soviet citizens accused of having collaborated with the Germans.

After the Krasnodar trial, the Kharkov took place between December 15th and 18th that same year. This trial was against three captured German solders and another Soviet citizen accused of being a German collaborator. The conditions of these two trials were quite similar—and what were those conditions? Only what you’d expect from Soviet Russia.

These trials were so blatantly unjust that they have been criticized by mainstream historians that follow official Holocaust doctrine. Franziska Exeler, Research Fellow at the Centre for History and Economics and Junior Research Fellow at Magdalene College, University of Cambridge, states:

Contrary to what the 1943 Krasnodar trial suggests, the majority of Soviet civilians accused of collaborating with the Germans were prosecuted in secret, in trials that lacked the basic principles of the rule of law. As part of pre-trial investigations, the secret police routinely subjected the accused to psychological or physical torture, most commonly beatings. Some trials were open to the public. During the Red Army’s reconquest phase, these public trials were often conducted within a few hours, outdoors, and in front of village audiences. Subsequent public trials of alleged wartime collaborators were more carefully prepared in advance, usually took place in large buildings like theatres or clubs that could accommodate hundreds of people, and over the course of several days. They closely followed the model that was established at the 1943 Krasnodar trial.

At these public trials, the authorities took great care to project a high degree of legality, which always included the presence of witnesses and defence attorneys. Yet while some, maybe even many of the convicted, had probably committed all, some, or similar acts that they were accused of (which distinguished Soviet collaboration trials from the public treason trials of the 1930s, at which the crimes were often imagined or fabricated), that did not make the collaboration trials any fairer. On the contrary: The authorities determined prior to a trial that the defendants would be declared guilty; in question was merely what sentence they would receive. During and after the war, the Soviet legal system continued to lack fundamental standards of rule of law-based legal systems such as independent lawyers and judges that form the precondition for any trial to be considered as impartial as possible. As such, then, Soviet justice was unable to establish the criminal responsibility of the individual on trial – although the extent to which this might have mattered to people in the audience who had suffered under German occupation is another question.

These are excellent points, Franziska, but we really can’t assume that the accused were guilty when they weren’t given a fair trial. It’s pretty obvious why she made the distinction that, unlike in the 1930’s, the alleged crimes of the Germans and their collaborators were not imagined or fabricated. She is a Holocaust affirmer after all. They have to walk a fine line when criticizing the USSR and maintaining a Holocaust narrative that heavily relies on Soviet reports.

The lack of the Soviets impartially examining evidence is problematic for claims the Soviets made. For example, the idea of Germans using homicidal gas vans was introduced during these show trials. I use the word “idea” precisely because it is just that—an idea. There was no physical or documentary evidence of gas vans before the trial, during the trail, or after. Instead, the “evidence” for the gas vans relied purely on testimony—coerced testimony from a show trial where the defendants were tortured. Later on, the IMT introduced documents to corroborate the existence of the alleged gas vans. Problem is, these documents were of dubious origin and contained impossible claims. Check out the revisionist Holocaust Encyclopedia for more information on that.

Other claims made during the show trials have also been adopted into official Holocaust canon, including the claim below of 30,000 Soviet citizens being murdered in gas vans, hung, shot, and tortured to death. There is no independent evidence that can verify this claimed death toll.

In fact, the Soviets tried to present a drawing as photographic evidence of mass casualties. I’m certainly not going to blindly trust what the Soviets claim about anything.

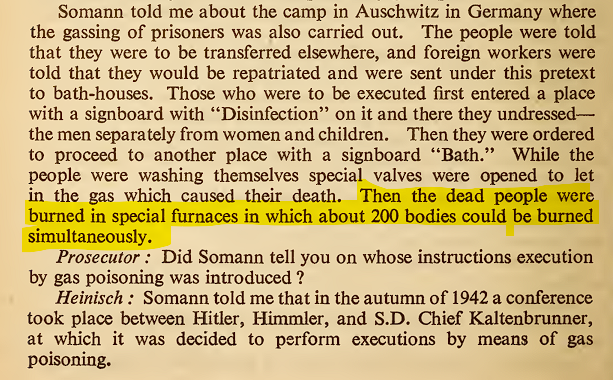

There were also absurd claims that the broken-down defendants testified to. These are claims that the Holocaust officials won’t address and instead they hope you don’t notice them. From Germar Rudolf’s Nuremberg book mentioned earlier (pages 49–50):

The three German defendants were groomed to make all kinds of absurd statements. Among them,

what Hitler supposedly ordered (how would they know?), and how gassings at Auschwitz were being carried out: by suddenly switching showers spouting water to emit gas instead. This preposterous nonsense demonstrates once more the ludicrous nature of these Stalinist show trials.

You don’t have to take our word for the absurdity; the transcripts are available online. Here where they’re talking about the special gas valves there is a claim that 200 bodies could be burned at a time in special furnaces. There sure were a lot of special things in Auschwitz! All kidding aside, there were only 46 ovens between the four largest crematoria, and they were designed to burn one body at a time.

Holocaust narrative enjoyers may be thinking, “Of course the Soviets had show trials, but the American and British let true justice prevail.” Those people are dearly mistaken. Stay tuned for part three to find out why!